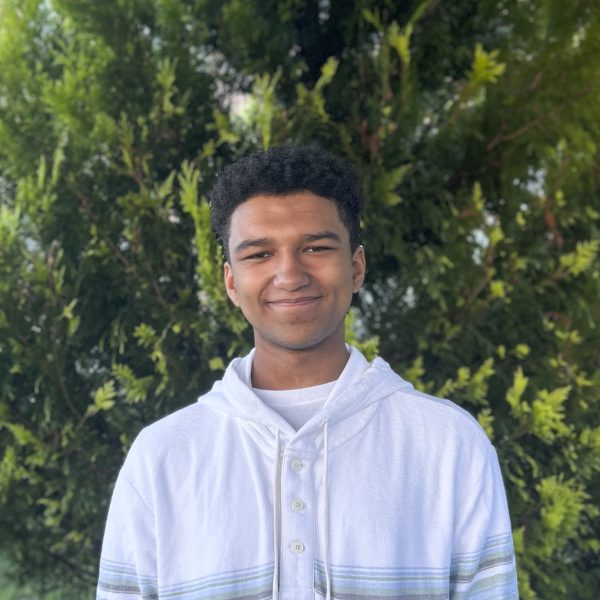

Shaded by a woodland canopy, intent on ushering salamanders to safety or cataloging mushrooms, junior Alex Karasoulos is in her natural element.

Although she’s still in high school, Karasoulos has found her passion. Since the age of 14, she has worked to conserve endangered salamander and mushroom species often overlooked by modern scientists. This involves leading groups of naturalists across numerous states to document gene pools and better understand these species.

Karasoulos has followed her curious instincts since early childhood.

“I’ve always just been fascinated with reptiles and amphibians,” Karasoulos said. “It initially started when I used to go to these reptile shops when I was 4 years old and I would just stare at the snakes and stuff because I found it really interesting. As I got older I started keeping them [reptiles] and I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, how cool would it be if I could find one out in my yard?’”

It was difficult to find salamanders in urban Winchester, so a move to more rural Southborough when she was 14 brought Karasoulos a lot closer to nature. Her eyes were opened to the expansiveness and complexity of everything around her.

“My main goal was to figure out ‘What is that? I see that plant, but what is it?’” Karasoulos said. “Every single thing I saw, every ant, wasp, flower, fern, mushroom. In the process of learning about them, I started to learn as a whole how nature worked.”

Salamanders in particular have always intrigued Karasoulos and have become a focus of her work as a naturalist. Whenever she would visit her great aunt’s house, there was no cell service or anything to do, the worst nightmare of an average 6 year old. But for Karasoulos, it became an opportunity.

“How many salamanders can I find in a day after hours of searching?” Karasoulos would ask herself. “This one is red and bumpy and this one is black and long and thin, and I’d find them in different places and just kind of learn what they were and their life cycles.”

The lack of information about salamanders and mushrooms is something that stood out to her.

“Just in general, in the United States a large portion of money goes towards conserving species in peril,” Karasoulos said. “These species are sensitive species, but the thing is the sensitive species are usually the ones that go most unnoticed.”

Karasoulos has gained vast knowledge on these species, despite the limited existing resources dedicated to them.

“Mushrooms are the big [sensitive species] because fungus is the last group, taxonomically speaking, that we don’t quite know anything about them, really,” Karasoulos said. “There is no protected fungus species in Massachusetts… And then for salamanders they can be a bio-indicator because they’re an extremely sensitive species. If the habitat is degraded then they can oftentimes disappear. In cities it gets extremely hard to find salamanders.”

What Karasoulos does know has stemmed from the network she’s created. She found herself reading books and not understanding complex terms, so she would reach out to the author or attend events.

“It’s just being really attentive and joining lots of clubs,” Karasoulos said. “Just trying to be outgoing and talk to as many people as possible. It’s the mindset that I try to have and it’s helped me a lot because the more people you know, the more you can help out with what they’re doing.”

Karasoulos spends up to 30 hours a week in the winter volunteering, although her overall conservation effort and enthusiasm is year-round. Much of this time is spent collaborating with others.

“You can try to learn as much as you want by reading as many papers as you want, but it’s still not nearly as valuable as the knowledge you get from talking to someone else,” Karasoulos said.

Freddie Gillespie is the chair of Southborough’s Open Space Preservation Committee where Karasoulos has volunteered for over two years. Gillespie, who had previously only known Karasoulos through Facebook groups, recounted seeing her for the first time.

“I knew her before I met her; I actually thought she was someone else, that she was older because she’s very smart in our field,” Gillespie said. “I thought she was someone in their twenties and maybe working in a science field. When I met her and I found out she was in high school, I was kind of blown away.”

They met at a talk held by Dr. Robert Gegear, a biology professor at UMass Dartmouth who shares his knowledge on at-risk pollinators at events in Northborough, Southborough and surrounding communities.

“At the end of the presentation we introduced her [Karasoulos] to Dr. Gegear,” Gillespie recounted. “Dr. Gegear said, ‘Oh, I want you to be in my lab, to be my grad student.’ And I go, ‘Well, she’s only in high school Rob.’ He goes, ‘Well, I’ll have to wait a few years!’ So she impressed him to that level by just talking to him for a few minutes.”

Gillespie’s praise for Karasoulos is immense.

“It was incredible and she just didn’t take it like it was any big deal; I don’t know if today she would even remember it,” Gillespie said. “She likes what she does but is not being a big shot about it.”

Karasoulos plans to major in biology and someday travel the world studying and saving salamanders, mushrooms and anything else she can.

“I think that’s really the plan and just help as many species as I can,” Karasoulos said. “Because at the end of the day I believe that, in general, you want to leave the world better than how you found it… If I could have saved something from disappearing forever that’s something I’d consider a net positive of being around for.”