What makes the grade

Differing grading policies affect students

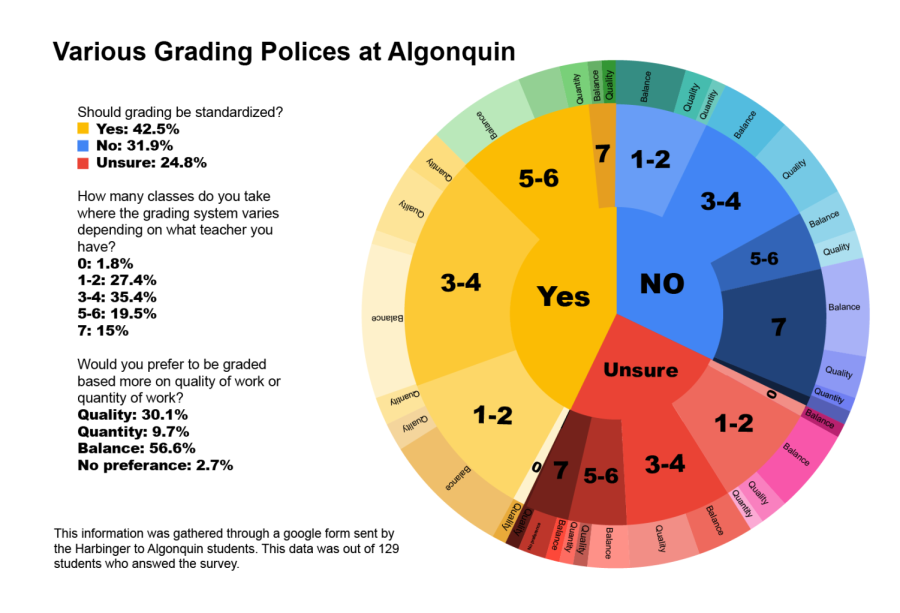

This graphic represents the percentage of students who answered each option in the Harbinger survey of 135 students from May 3 to May 8 through Google Forms.

June 23, 2022

Teachers have the freedom to develop their own grading policies to create a more individualized experience, but inconsistencies within the same course can cause frustration for many students.

Students have a variety of course options with different levels and focuses, but one common thread between the majority of classes is the freedom teachers have to create a unique experience for their students using their own grading policies and teaching styles.

According to a Harbinger survey of 135 students from May 3 to May 8 through Google Forms, 98% of students take at least one class where grading policies vary depending on what teacher they have, and 71% of respondents said they have three or more classes where grading policies differ depending on their teacher.

“I think teachers really appreciate having autonomy in how to both plan their course and assess students’ progress,” Principal Sean Bevan said.

English teacher Seth Czarnecki agrees that teacher autonomy is a major advantage of not having a standardized grading system.

“There’s a lot in education that feels really paternalistic and that people outside of an individual teacher’s classroom think they know more what’s best for that teacher’s students and don’t really trust the teacher to be a professional and to be a student of the game,” Czarnecki said.

He also believes that discussing differences in grading policies and philosophies can be considered taboo for some teachers.

“Grading is almost like the third rail of teaching philosophy,” Czarnecki said. “It’s a thing that a lot of teachers don’t really discuss with each other because for some reason, people feel like it’s very personal.”

Students are split over whether or not grading systems should be standardized for a course. In the Harbinger survey, 42% of students think teachers should be required to use the same grading system and requirements, 31% of students think teachers should have autonomy over their grading and 27% are unsure.

“[Teachers having the ability to create their own grading policies can make it] difficult to compare with peers to evaluate one’s own standing in terms of ability and development at times,” one survey respondent wrote. “It can definitely be frustrating and trespass into the field of unfair, particularly because a student with a lenient teacher could get higher grades than another student who puts in more effort but has lower grades — all of that due to the person they have as their teacher.”

Numerous survey respondents shared the notion that differences in grading policies feel unfair.

“It adds a luck factor into GPA,” one student wrote.

Many students who support a teacher’s ability to create their own grading system recognize that this ability allows teachers to tailor their policies to their class in a way that works and is most beneficial for them.

“The creation of teachers’ own grading systems and requirements allows them to better accommodate the needs and abilities of their students,” one survey respondent wrote. “It gives the teacher more weight/importance in the content they teach because it’s not being specified/restricted/constrained by a higher authority.”

With the freedom teachers are given, they are able to create many different kinds of assignments. World Language Department Head Nicole Demember and English Department Head Jane Betar both explained how a variety of different kinds of assignments are beneficial to students and implemented in their departments.

“It’s important for [students] to know how to take a traditional exam as well as give presentations, speeches, and produce something that demonstrates their understanding of the newly learned material,” Demember said via email.

Betar believes that variation in assignments keeps students interested in learning.

“If one assignment doesn’t tap into their interests and strengths, another kind of assignment might. Choice is also important sometimes too,” Betar said via email. “I try to alternate my assignments/assessments from more traditional academic writing to creative and personal. I also like to give students opportunities to write about something that is not related to the text they are reading in class.”

Administration and teachers have made an effort to standardize some grading policies this year. Bevan explained that this year was the first year that midterms and finals are standardized for each course. According to Bevan, standardizing those largest tests helped create a balance between giving teachers freedom in their teaching and ensuring students were being taught the same standards and evaluated in the same way.

“This year we talked a lot about …the big assessments … as a way to at least ensure that kids are halfway through the year learning the same things and being tested on the same things,” Bevan said. ”If the policies and practices are a little bit different in the meantime, in the parts of the year leading up to the midyear or from the midyear to the final… that’s the balance we were happy with this year.”

Teachers maintain the freedom to develop their own grading policies that reflect their own values and philosophies for each term’s grades.

“Teachers have a lot of autonomy in how they assess student progress, and that has worked well for a long time.” Bevan said via email, “So, I don’t anticipate making any immediate changes.”

Some teachers’ grading philosophies value quantity of work over quality of work, while others’ philosophies value a balance of the two.

The Harbinger survey showed that 55% of students prefer to be graded based on an equal balance of quality and quantity of their work. Thirty-two percent preferred being evaluated based on just quality, and 11% preferred being evaluated only on the quantity of their work.

Sophomore Austeja Bazikas believes grading should be based on quantity.

“If you do 100% of the work and you give your best effort I think you should get an A or B at the least,” Bazikas said. “Some students are … better at a certain topic and they can not put in a lot of effort and still get a better grade than students who are putting in so much more effort.”

However one survey respondent stresses the importance of focussing on the quality of student’s work.

“Some teachers are hardcore graders while some teachers in the same department as them grade based on participation. I find it highly unfair for the students who have a particularly low grade in one subject because they have that one teacher who grades hardcore and on accuracy while their peers have a higher grade in the same subject and have a teacher who grades on participation.” One student respondent wrote. “Like, a kid could be [barely trying on] an assignment for a teacher and still get a 100 and earn an overall A+ in that class that they could be failing and a hardworking student settles for a B in a class where they use hard core grading.”

Bevan believes that classroom environments where students know what is expected of them to achieve success is most beneficial. He also believes that assessments should focus on a student’s long term understanding of a topic rather than their short term recollection of facts.

“What I have asked department heads and teachers to really think a lot about, is to come to common agreements and understandings of the standards that students should achieve mastery of, and then assess students on their progress towards those mastery standards,” Bevan said. “How they assess I’m not as worried about, because I do believe that teachers know best.”