Grades may not reflect intelligence

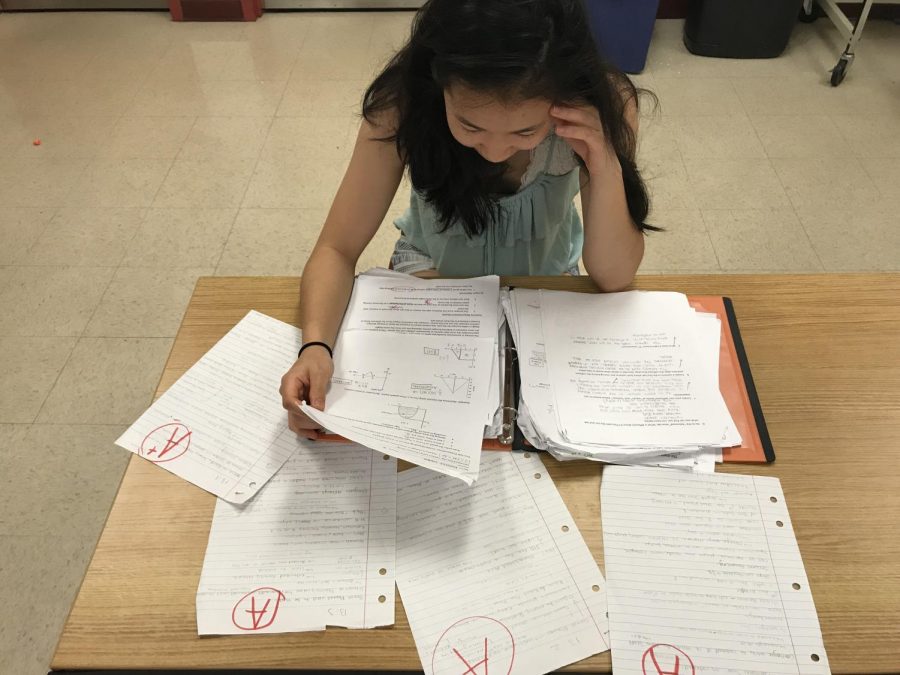

Junior Nellie Zhang stressing about finals despite her great grades.

December 5, 2015

Grades do not always represent a person’s intelligence, according to many students and teachers, because many other factors determine the outcome of a letter grade.

“Tests, quizzes, classwork assignments, homework, and participation, all of those things add up to a certain number of points that leads up to a student’s grade with it,” social studies teacher Justin McKay said. “A lot of it is done particularly by the student.”

“I’ve had my own personal experiences where I haven’t understood something and I had to work really hard to figure it out and I got there,” science teacher Elisa Drake said. “I watch students on a daily basis who are very intelligent but don’t do the work, so they don’t get great grades. I have students who don’t have super natural ability and they work super hard and get fabulous grades.”

Some students think the meaning of the material is lost when more emphasis is put on memorizing information instead of learning it thoroughly.

“[Grades] depend on the test and how good of a test taker you are, and I find that bad,” sophomore Bridget Brady said. “If you aren’t working hard, you aren’t learning or producing your best work. So you’ll be all set for that test, but not for life.”

Many teachers agree that grades are often a result of laziness rather than academic capability.

“Over the many years that I’ve taught, there have been a number of students that, as a teacher, you want them to achieve more for themselves, [but] they have not done the work necessary enough to get the best grade they possibly can,” McKay said.

According to Principal Tom Mead, if students strive to fulfill their academic responsibilities, it should be possible to obtain high marks.

“We try to put courses together at different levels of rigor and depth to challenge every one of our students individually,” Mead said. “We want all students to have a realistic opportunity, through their work and through their effort, to get an A or a B in a course.”

Low grades can indicate specific problems, and students can use their understanding of these issues to help reflect on the factors of their lives that contribute to a grade.

“I don’t necessarily believe that grades identify how smart you are, but I think grades particularly show you some warning signs of things that are getting in your way…If you’re getting a lower grade, there’s something missing…whether it was a lack of effort, whether it was problems at home, [or] something else that distracted [the student],” McKay said.

Grades in high school do not always correlate to future success of full potential.

English teacher Deborah Saltzman told of a brilliant boy she had freshman year who lacked effort. By senior year, his grades were so low he didn’t get into the college that he had his heart set on attending. Yet, with hard work, he managed to transfer second year to an Ivy League school.

“The student you are your freshman year doesn’t necessarily predict who you are going to be,” Saltzman said.

Although they acknowledge that schoolwork is important, many teachers realize the talents students have in other areas that are not necessarily tested in a school setting.

“We don’t measure here every kind of intelligence…You’re not always asked in a school setting to demonstrate that intelligence across a broad spectrum of intelligences,” Mead said. “[Just because] students are not successful in school doesn’t mean they can’t be or won’t be successful in life.”

“You need to be a well-rounded person in life,” Drake said. “Grades and academic achievement is only one aspect of life.”