Fighting the sign language stigma

Being the child of deaf parents provides perspective

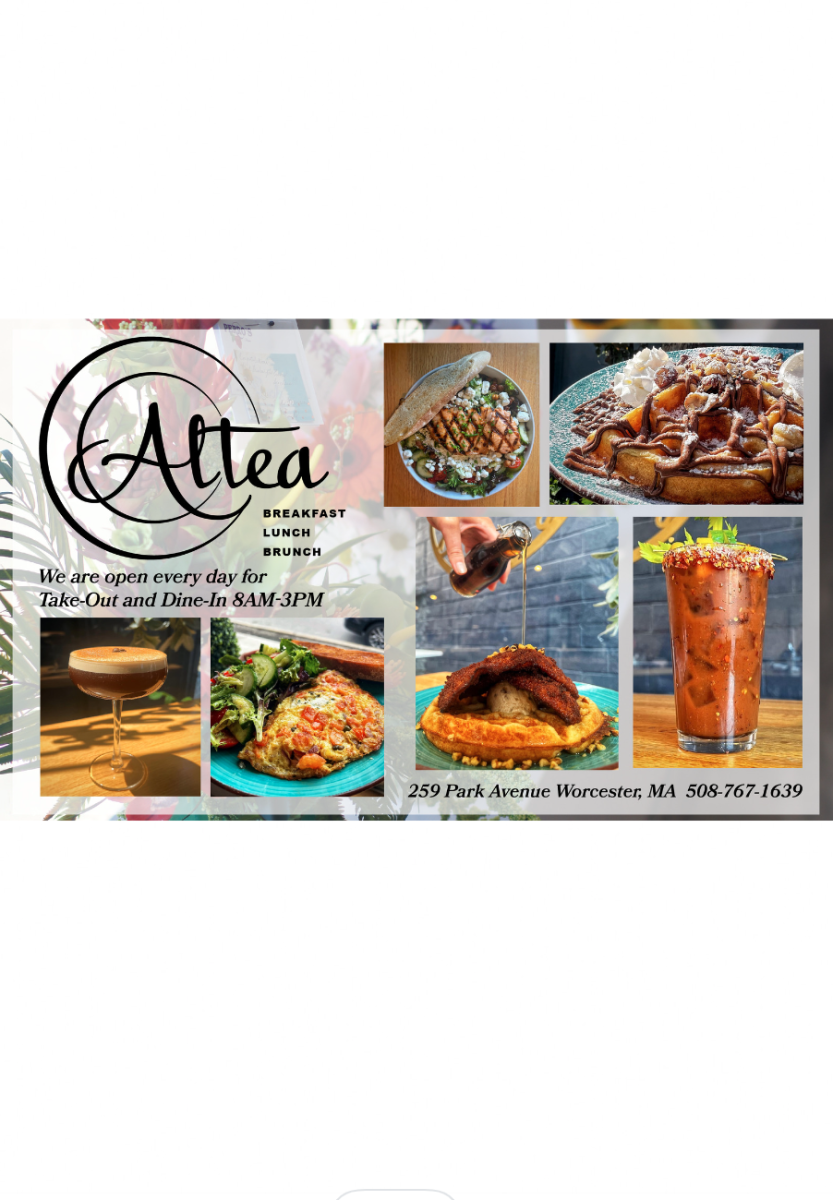

Columnist Sven Patterson demonstrates how to sign “hello.” Learning just a few simple signs can indicate compassion and a willingness to communicate with members of the deaf community.

June 19, 2015

“Can they drive?” “How do they take care of themselves?” “Can they read and write?”

These are the questions that drive people to assume that I harbor alien creatures in my own household, and that I’m one of the few people who can break the communication barrier with them.

My parents are deaf, meaning they lack the ability to hear sounds. This makes me a KODA, or a Kid of Deaf Adults. My first language is American Sign Language, not English. My parents are also completely able-bodied individuals who can read, write, and even drive. Yet as I see my parents move through the world, I have noticed that there is a stigma that exists against deaf people.

First, let’s talk about some small stuff. For no apparent reason, people have an extremely hard time talking to deaf people more than any other speaking individual (figuratively and literally). People act like a deer in headlights in front of my parents. They will stare at my parents like they have glowing arrows pointing right at them, but as soon as they have to interact with them, they want nothing more than to run.

There have been people who blatantly make fun of how my parents speak to each other. They will try to fidget their hands in a way that mimics my parents, or move their hands in a wild flurry of fingers and ask “Is this a sign?” It’s almost like saying nvk!@hgl;ifӁg and asking if I said anything in Swedish.

My parents are really not all that different though. Most deaf people have dealt with the hearing world their entire lives and are more than willing to try and talk with you. My parents are overjoyed when someone really tries to talk with them because it shows that they have taken the time to care about what they have to say. However, yelling never works. Ever. They’re deaf already; they won’t get any less deaf.

A really good way to talk to them is to speak a bit more slowly and clearly to give them a chance to try to understand what you said. Maybe even pick up some of the language if you really want to talk to them. Online videos and resources are everywhere today, and knowing even a couple signs shows a huge amount of respect.

Now for the harder hitting problems. Oppression is a word that sparks anger and hatred in most people, although many don’t have to deal with its effects for themselves. My parents deal with oppression every single day. People get angry because my parents are “ignoring” them even though they never knew anyone was talking to them in the first place. I’ve seen mall greeters talk behind their backs because my parents had no idea there was even someone there. They are left out of entire conversations because no one cares enough to translate for them.

Deaf people are denied their basic rights every single day. Hospitals often won’t provide interpreters for a deaf patient (which is illegal, by the way) because it’s too much of a hassle. Police who encounter deaf people usually don’t know how to react. If they need to handcuff them, it limits their only means of communication, but this causes some officers to look at any attempts to communicate as an act of aggression, which often makes things spiral out of control.

Being a KODA has opened my eyes to the fact that many people are shut into their own little world. The preconceived notion that is shared by so many people is that as long as they can’t see that a problem exists, then it simply doesn’t. Even though I’ll laugh at the fact that no, I don’t actually “talk” to my parents, or that people make up cute little signs for words that make no sense, the tough truth is that our actions have a much bigger impact than we think they do, for better and worse.

We have to look at how we treat not only small communities, but how we aim our respect towards humans as a whole. Even though you might not care about some random people who struggle with their own issues, are part of another social group, or can’t hear, these voices do matter, and they deserve to have their voices heard, or their hands watched.