Community strives to support, educate students about sexual assault and harassment

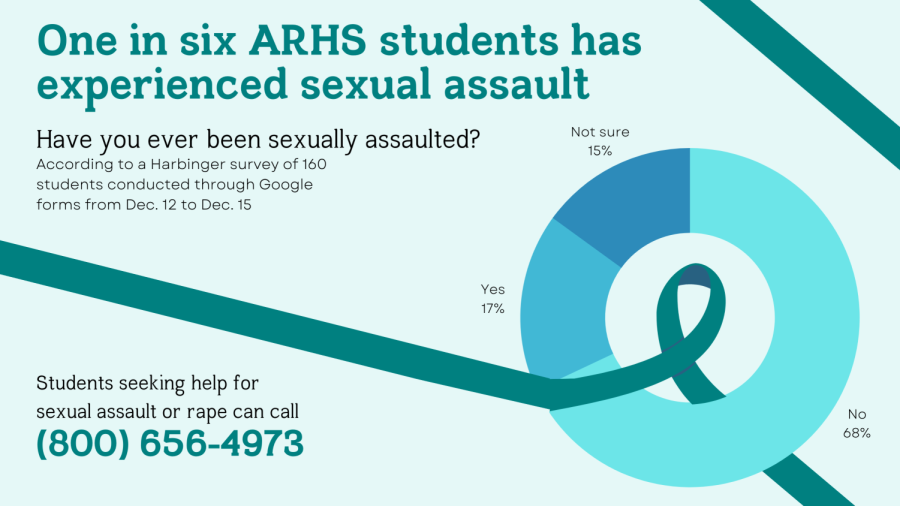

One in six ARHS students has experienced sexual assault. The community hopes to address this issue through support systems and consent-positive curricula.

March 1, 2023

Sexual harassment and assault are problems which, according to local statistics and national averages, disproportionately affect high school girls. Algonquin aims to address these issues through a combination of support systems and consent-positive curricula.

In 2019, a Harbinger survey of 236 students found that 15% of ARHS students had been sexually assaulted in some way. Today, four years later, sexual harassment and assault statistics remain just as concerning. According to a 2022 Harbinger survey of 160 students conducted through Google Forms between Dec. 12 to Dec. 15, 17% of Algonquin students say they’ve experienced sexual assault.

According to Principal Sean Bevan, although student reports are infrequent, any alleged incident of sexual harassment or assault brought to administration immediately becomes the top priority. In the case of a report, Bevan promptly involves the Title IX Coordinator, local law enforcement and the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF), as it would constitute a form of abuse.

“It’s the kind of thing that when it comes to our attention, we drop everything,” Bevan said.

According to the survey, 10% of respondents said they had experienced sexual harassment, assault or abuse while at school. Senior Jaclyn Faulconer is among those whose assault occurred on school property.

“I was assaulted once in this school during school hours,” Faulconer said. “It definitely made me scared to come to school, because I knew that person would continue to assault me or retaliate if I reported it.”

Despite her fears, Faulconer did report the incident to an assistant principal, which was her first step in feeling comfortable in school again; however, the experience had a lasting negative impact on her.

“It definitely affected me,” Faulconer said. “I became very skittish to be around everyone. But I think the administration handled it the best that they could have done.”

Sexual harassment is much more common experience than assault, especially amoung females in the Algonquin community. The US Department of State’s Sexual Harassment Policy defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature. According to the Harbinger survey, 54% of female students responded that they had experienced sexual harassment.

Senior Jay Guarino, a non-binary victim of sexual assault, was not surprised by these statistics.

“[The survey results] make sense, unfortunately,” Guarino said. “It sucks that we as people are often desensitized to [sexual assault], but I feel like it’s fairly common. There’s a good percentage of people who don’t even realize it happened to them.”

Although freshman Lana Ingerslev believes sexual harassment, such as catcalling, occurs more frequently in crowded cities, she has also experienced it in her hometown since middle school.

“I’ve gotten honked at twice while running in Northborough in seventh or eighth grade,” Ingerslev said. “It’s not fun.”

The effects of sexual harassment vary drastically depending on the person. Some Algonquin students are able to ignore or brush off the harassment altogether, but for others, it is much harder to forget.

“I’m a lot more cautious [after experiencing catcalling],” an anonymous sophomore said. “I’m a lot more self-conscious. I’m a lot more self aware. I take a lot more care of my safety and sometimes I carry a self-defense keychain.”

Junior Oliver Kubik has often experienced and felt uncomfortable by the way some students turn sexual comments into jokes.

“If [the punchline is] sexual harassment, it’s not the right thing in my opinion,” Kubik said. “Sexual harassment is not a joking matter.”

In order to promote consent-positive education, sophomore health classes dedicate a unit to discuss its importance. Junior Milla Santos reflects on the unit as being a good learning experience and believes it is an important topic to learn about.

“We watched a video comparing consent to drinking tea,” Santos said. “I thought it was a good way of showing it, even though I already knew what consent was.”

According to health teacher Melissa Arvanigian, health education at Algonquin tends not to go into specifics about sexual assault, but works to provide students with the tools they need to find help, including the importance of sharing what happened with a trusted adult and going to a hospital right away for a rape kit.

“I always say I don’t care if you guys are completely just about to do something and one person decides they’re not comfortable, you need to respect that because no means no,” Arvanigian said. “But also being advanced upon without your consent is definitely something that you should be speaking to somebody else about. Don’t just sit back and think it’s okay for someone to touch you when you don’t feel comfortable. It’s your own body. People need to understand that, and they need to respect that.”

According to the US Department of Justice’s definition of dating violence, it is an act of violence committed by a person who is or has been in a romantic or intimate relationship with the victim. In addition to consent, students learn about the importance of healthy relationships in their sophomore health classes to understand the development of abusive environments.

“I do what’s called the progression of an unhealthy relationship with an acting skit,” Arvanigian said. “I show them all the warning signs from how innocent it looks in the beginning to how it progresses to pretty severe towards the end.”

Sexual assault is also covered in other parts of Algonquin’s curriculum, particularly in the English department through some of the texts read in various courses. English teacher John Frederick addresses the topic with books in some of his courses.

“Literature is a reflection of life and interesting stories often have adversity involved just like in life,” Frederick said. “I think it’s important to address what obstacles we face in life, how to better deal with it, or prevent it from happening.”

One book he often incorporates into his Freshman English classes is the 2016 novel “Beartown,” whose plot follows the rape of a 15 year-old girl perpetrated by another student and the ensuing controversy. Fredrick hopes to be able to teach all of his students about the importance of consent.

“I hope my students leave the room saying there is no excuse for it,” Frederick said. “It’s not the girl’s fault. It doesn’t matter what she is wearing, or what time of day it is, or where she is or how much she had to drink.”

With the recent release of “She Said,” a film about the journalistic coverage of sexual assault in Hollywood, conversations about the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment and assault have been reignited both in and outside the classroom.

“It’s something that I think is important to talk about,” Frederick said. “I’ve never been afraid to talk about tough issues with young adults. I think there is a way to handle those conversations that is appropriate, that’s respectful, and not intended to make anyone feel uncomfortable.”

While jokes may not seem harmful on the surface, unwelcome comments are a form of harassment. The article “How to Talk to Your Students about Harassment” recommends to tell the harasser to stop the joke or unwelcome behavior, write down details about the encounter and report it to a trusted adult or administrator.

“Students should always go to any trusted adult,” Bevan said. “They need to let an administrator know right away, so we can make sure they are safe and get the help and support that they need.”