Racial disparities in death penalty reveal significant issues with justice system

Assistant Opinion Editor Juliette Piovoso writes about the racial injustice present in the death penalty — particularly the Julius Jones case.

November 30, 2021

When Julius Jones was 19, he was convicted of a murder he claims he did not commit. Sentenced to death in 1999, Jones has suffered the consequences of his supposed actions, banished to solitary confinement for 23 hours a day.

However, on Nov. 18, 2021, Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt granted clemency to Julius Jones, halting his execution. Stitt commuted Jones’ death sentence just hours before he was scheduled to be executed for a killing he maintains he did not commit.

Julius Jones’s long-standing assertion of innocence attracted worldwide attention, including public outcries from celebrities such as Kim Kardashian West and Cleveland Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield.

The undeterred uproar from activist groups backed Jones’s innocence, stating vital evidence to prove he was innocent.

According to the Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to exonerating individuals who have been wrongly convicted, “Julius Jones was at home having dinner with his parents and sister at the time of the murder; however, his legal team failed to present his alibi at his original trial. His trial attorneys did not call Mr. Jones or his family members to the stand.”

Alongside a valid alibi, Jones does not match the description of the person who committed the crime, which an eyewitness provided.

Most notably, the other witness, Jones’ accomplice Christopher Jordan, claimed that he was the getaway driver while Jones killed the man.

Despite the fact Jordan’s appearance matched the eyewitnesses’ hair description, “in exchange for testifying that Mr. Jones was the shooter, Jordan was given a plea deal for his alleged role as the “getaway driver,” according to the Innocence Project. He served 15 years in prison and is now free.

“Three people incarcerated with Mr. Jordan at different times have said in sworn affidavits that Mr. Jordan told each of them that he committed the murder and framed Mr. Jones,” according to the Innocence Project.

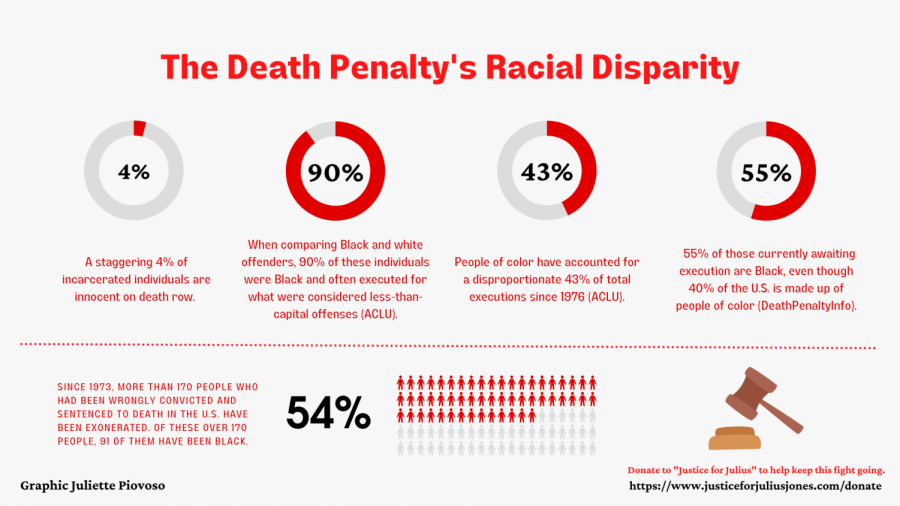

A staggering 4% of incarcerated individuals are innocent on death row, and in Julius Jones’ case, the 41- year old convicted killer might just be the exception.

The impact of racial bias in Jones’ case is too disturbing not to ignore. Not only were 11 out of 12 people serving on the jury white, but one juror referred to Mr. Jones by a racist slur, suggesting that he be taken out behind the courthouse and shot.

Yet, these inconsistencies are not solely a reflection of the corrupt individuals involved— it is a magnification of the flawed and inequitable criminal justice system that viciously strikes any person of color.

Although Julius Jones was granted a pardon, thus resulting in him not being put to death, the 41-year old will now serve life in prison without the possibility of parole, as directed by Governor Stitt.

Life in jail, without a mere retrial for a crime that has substantial counter-evidence to exonerate Jones? Does this surprise you? If it does, unfortunately, it shouldn’t. This injustice has been reused and recycled since the very beginning of our country’s application of the death penalty.

People of color have accounted for a disproportionate 43% of total executions since 1976 and 55% of those currently awaiting execution (even though the U.S includes 40% of people of color.)

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “Since 1973, more than 170 people who had been wrongly convicted and sentenced to death in the U.S. have been exonerated.” Of these over 170 people, 91 of them have been Black.

According to an April 2001 study by researchers from the University of North Carolina, when looking at homicide cases, “the odds of getting a death sentence increased three and a half times if the victim was white rather than Black.”

In addition, the American Civil Liberties Union also condemned the death penalty by citing evidence from The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

As stated by the non-profit organization, “comparing Black and white offenders over the past century, many were often executed for what were considered less-than-capital offenses for whites, such as rape and burglary. (Between 1930 and 1976, 455 men were executed for rape, of whom 405—90 percent—were Black).”

Our nation is making considerable strides through public advocacy and protests: we collectively raised awareness of Mr. Jones’ wrongful conviction, stopping his execution. However, this is not enough.

To initiate change and help support Julius Jones’ fight for justice, you can:

- Sign the petition and demand justice in his case.

- Follow Justice for Julius on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

- Donate to “Justice for Julius” to help keep this fight going.