Money jeopardizes fairness of standardized tests

Staff Writer Kayla Albers writes that standardized testing is too expensive of a system to be one of the main pieces of criteria in college admissions.

January 2, 2020

Each year, as the college deadlines approach, applicants are forced to fill in many students’ most dreaded number: scores received on standardized tests.

Whether it’s the SAT, ACT or even state standardized tests such as Massachusetts’ MCAS, students across the U.S. take the same version of an exam, with the objective of fairly comparing scores, hence the name standardized. Despite the system’s attempt at giving students an “equal shot” at success, exams such as the SAT and ACT are limiting. Kids in less fortunate parts of the country don’t have access to test preparation and face inferior education systems than we have in Massachusetts, and even for students who come from places with more advantages, their test scores might not accurately represent their abilities.

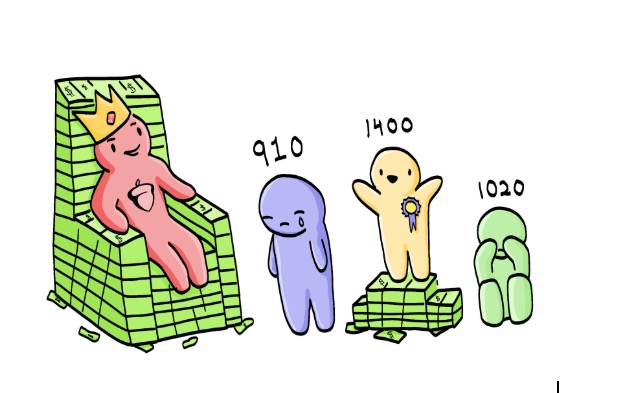

Companies such as The College Board make egregious profits from exams at the expense of families around the country. Despite 38.1 million U.S. citizens living in poverty, exams cost obnoxious amounts of money. With AP exams costing $106 each, and SATs at $47.50 with optional essay for $64.50, profits add up. Although fee waivers and reductions are offered for those with documented need, The College Board still generated $1.1 billion of revenue in 2017.

While exams might test intellectual abilities to some degree, they don’t prepare students for the future: the goal of education in the first place.

Teachers are pressured to “teach to the test” in that they target specific curriculum covered on exams, neglecting other curricula and limiting students’ education. According to a national study recorded by the Center on Education Policy in 2007, 44 percent of school districts reduced time spent on sciences, social studies and the arts by an average of 145 minutes each week to place focus on math and English curricula. This lack of wide-ranging education puts students at a great disadvantage. While students might not have interests in math or English, they are forced to learn more expansive curricula in order to earn better scores on their exams.

The pressure students face to do well on exams affects mental and physical health. According to an article written for “The Sacramento Bee” by Susan Ohanian in March 2002, “test-related jitters, especially among young students, are so common that the Stanford-9 exam comes with instructions on what to do with a test booklet in case a student vomits on it.”

More and more colleges are becoming test-optional; more than 700 colleges are currently test optional, which decreases some of the pressure put on students but does not solve the problem.

While more fortunate students can pay for, and have access to, exam preparation classes, such classes focus on ways to trick the system. Yes, tutors are available, but the majority of students invest their time in learning how to take a test, such as the process of elimination.

Kids nation-wide should have the same advantages or lack thereof. If an exam is to be given, it should be given fairly. Students from less fortunate districts lack access to advantages such as classes and tutors and are being scored on the same exam given to students from more fortunate school systems who have access to exam preparation classes and tutors.

While standardized testing may make filtering through applications easier for boards of admission, the system should be altered or gotten rid of completely; standardized tests should not be imperative to one’s success in the future.