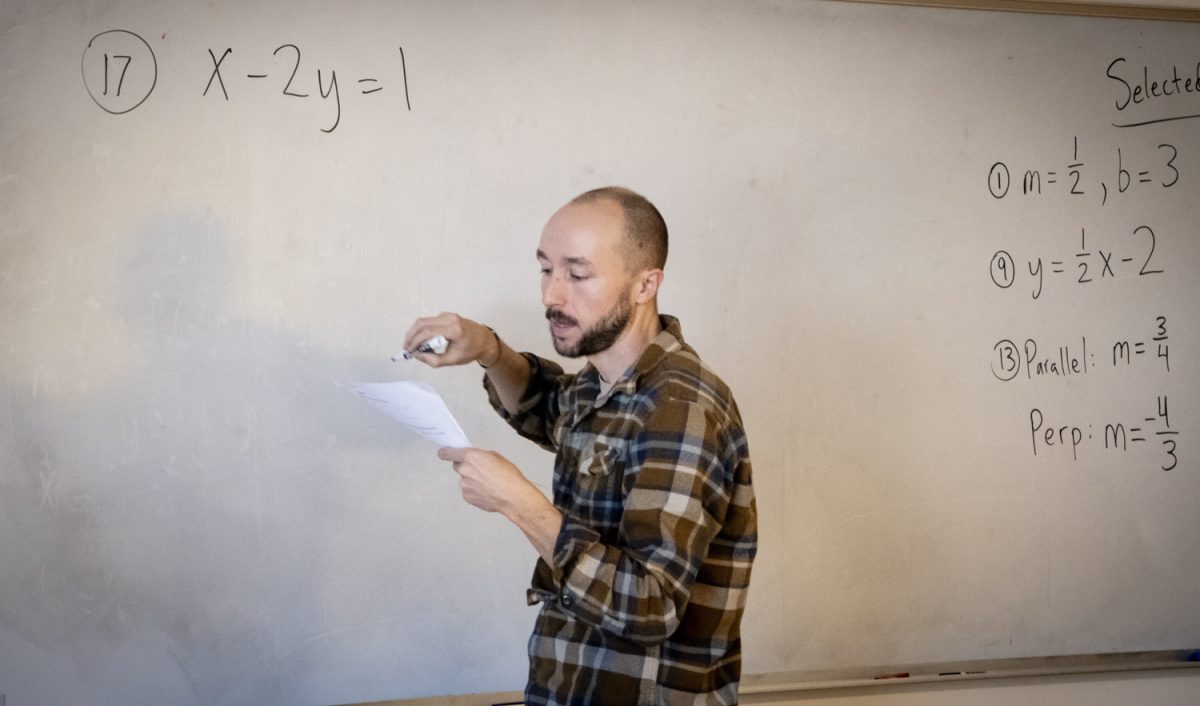

Dr. Mary Rose Steele, an experienced math teacher at Algonquin and recent Doctorate of Education graduate from Northeastern, is researching ways to support students with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

For many students with ADHD, it’s not a lack of intelligence or effort holding them back — it’s the inability to take the first step. This struggle, known as executive dysfunction, is often misunderstood.

Steele has taught at Algonquin for 24 years and is currently working on publishing her research about how teachers can implement strategies in the classroom to support students with ADHD, especially concerning executive dysfunction.

According to Steele, executive dysfunction is a problem with the brain’s ability to manage tasks.

“If you’re going to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, you know you need to get out two slices of bread, and need a knife to spread it with,” Steele said. “People that have difficulty with executive dysfunction have a difficult time putting the steps they need to take in chronological order to make that peanut butter and jelly sandwich come to life.”

Steele hopes her research can help teachers get an understanding of what’s going on in their students’ brains and allow teachers to better support them.

“Someone with executive dysfunction is typically viewed as lazy, which is actually not the case,” Steele said. “They’re not lazy at all. They just cannot put the processes together and put their first foot forward to start something. I think that’s a hard thing for a lot of people, especially neurotypical people, to understand.”

Understanding why students struggle with completing tasks has helped Steele implement strategies in her own classroom. Even undiagnosed students benefit from a learning environment tailored to their needs.

“I used to get super stressed out when students took their assessments outside my classroom or needed extra time, but the understanding I’ve gained from this population helped me so much better support them and care for them,” Steele said.

Since Steele started her research, she’s helped her students by giving them extra time on assessments and getting documentation to support them in all of their classes. Over the past 24 years, Steele has seen significant growth in awareness and accommodations for ADHD.

“There’s more students on IEPs and 504s (individualized learning plans) and that, I think, is proving that people are recognizing that something is wrong,” Steele said. “They know they can get something into place structurally to help them get through their school day. This is the age of information.”

Steele recognizes that despite the growing acceptance of ADHD and executive dysfunction, both subjects are still under researched, especially at the high school level.

“So many of these students feel bad about themselves and that’s why I want to help them,” Steele said. “It’s a hidden disability and they just wind up feeling like they’re stupid or inept. My biggest piece of advice is don’t feel bad about yourself.”