A donation of $40 or more includes a subscription to the 2024-25 print issues of The Harbinger. We will mail a copy of our fall, winter, spring and graduation issues to the recipient of your choice. Your donation supports the student journalists of Algonquin Regional High School and allows our extracurricular publication to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Emancipating silenced voices

English curriculum needs to incorporate diverse perspectives

March 2, 2018

Think of every book you have been assigned to read in high school: “Lord of the Flies,” “The Great Gatsby,” “Of Mice and Men,” “Romeo and Juliet.” Though these works of literature come from drastically different eras, what they do have in common is that they were written by white men.

Recently, the English department has noted the lack of minority authors in assigned readings. Despite that works of Shakespeare, Fitzgerald and Poe are considered to be hallmarks of great literature, should they still be covered extensively if it means that students will only learn from a single perspective?

In the Numbers

According to the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 80.8 percent of students attending Algonquin Regional High School were white in the 2016-17 school year. This figure is significantly high compared to the almost 60 percent of white people who enroll in schools statewide and suggests that the Algonquin population simply lacks ethnic diversity.

On its surface, there is nothing wrong with a racially homogeneous high school population; after all, it is something that is out of anyone’s control. But ultimately, it becomes a problem when students internalize the idea that the white male perspective is the most valid because it is the most prevalent. In this case, exposure to books by minority authors is essential.

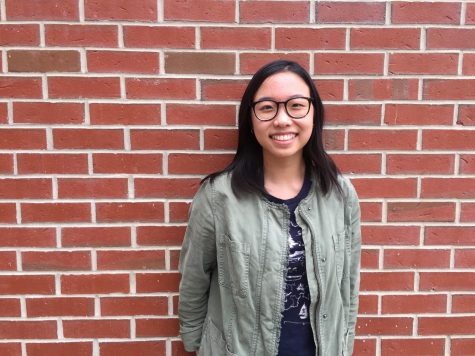

Harbinger editor-in-chief and AP English Literature student senior Cassidy Wang feels that the school’s lack of diversity could be ameliorated through introducing more diverse literature into the English curriculum.

“I definitely don’t think that we’re getting the full scope of the demographic of our society,” Wang said. “Our school-assigned reading curriculum is a way to bridge the gap between our bubble in the white community and the demographic of the real world.”

English teacher Monica Grehoski agrees that assigned reading could be a way to expose the school’s largely homogenous population to unfamiliar perspectives.

“I think that because our school wouldn’t be identified as one that’s diverse, particularly socioeconomically, I think that it’s critical that we read literature that shows a worldview different from our own,” Grehoski said.

Writing tutor and AP English Literature student senior Katie Hunter notes that although many students have read about racism, slavery and other minority experiences, the perspective from which they have read them is skewed.

“To hear about [racism] from someone who didn’t necessarily experience it is not as valuable as having it from someone who did, like reading a slave narrative,” Hunter said.

The Curriculum

In order to broaden the scope of assigned readings, the English department has tried to include works of literature written by authors with minority backgrounds.

“We’ve introduced more diversity into the curriculum,” English teacher John Frederick said. “In the freshman curriculum, we taught ‘Native Son;’ it was part of our core curriculum for many years.”

However, Native Son was eventually removed from the curriculum due to scenes that included violence. Interestingly enough, most assigned readings have varying degrees of violence, whether it be the brutal homicides in ‘Lord of the Flies’ or the emotional deaths in ‘Of Mice and Men.’ Thus, the question has to be asked: what separates violence in novels written by white men from violence as written from the perspective of an African American author? If one reading is removed from the curriculum because of violence, does that entail that all readings involving violence be eliminated as well? It only makes sense that all assigned literature is judged according to the same criteria.

Silenced Voices student senior Linear Dowd believes that novels should not be removed from the curriculum for the purpose of protecting students, especially since reading and analyzing texts serve as a platform for discussing current events.

“Why do parents want to shelter their children so bad from what’s real?” Dowd said. “Violence is real. We should be able to learn about it, read about it and have a discussion about it.”

Similarly, Wang acknowledges the importance of reading to learn about different types of people and their backgrounds.

“When we’re not exposed to diversity, we don’t know how to sympathize and engage with people of other backgrounds,” Wang said.

Ultimately, most books in the English curriculum are there because they are classics; the fact that they were written by white men happens to be a by-product. Hunter believes that the classics currently taught at school are extremely valuable to students’ educational experience.

“To get rid of something like [‘1984’] just because it’s written by a white male is just as bad as not having diversity [in literature],” Hunter said. “It’s less about who writes it, in my opinion, and more about what the literature tells you and the message you get from it.”

Nevertheless, the school should work to expand the scope of literature covered in English classes. There are many works of classic literature by women and people of color, including “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, “Love in the Time of Cholera” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, “Song of Solomon” by Toni Morrison, and “Little Women” by Louisa May Alcott. Students would certainly benefit if novels such as these were to be incorporated into their education.

Classic literature is defined by society, and there is an evident disparity as to which books are considered to be “classics.” This imbalance is reflected in students’ reading. Wang just read “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston this school year, her senior year.

“This was the first book I read in high school by a non-white person,” Wang said. “I think it’s really crazy that before this, I’d never read a book by someone different from us in school.”

Many students can probably relate to Wang’s experience. However, the school can work against this disparity by including more classics from different voices.

Solutions

Even with such a mission, there are restrictions that prevent the school from expanding the English curriculum. For instance, there are certain books that Massachusetts schools are expected to cover in their English classes. Additionally, the school’s budget cannot be completely allocated to purchasing new books.

Yet with technology and accessible information, classes can easily make adjustments to include a wider array of sources. According to Dowd, Silenced Voices teacher Emily Philbin teaches her classes by showing students lectures and pieces of music in addition to having them read books.

“I don’t think Ms. Philbin is using much of the school budget to teach what she’s teaching,” Dowd said. “We live in a world where you can Google everything.”

Another way to address the budget problem would be to assign diverse literature as summer reading, and then to slowly introduce one new book each year into the curriculum.

Though some students still may not bother to do the assigned reading, they can benefit from just being in class and hearing discussions. They will learn about the struggles and stories of those from different races, genders and sexualities by sitting in class and hearing their teachers and peers explore books that discuss these topics.

The purpose of education is not solely to teach, but also to help students develop into knowledgeable and informed global citizens. The English curriculum should be expanded to include works from minority authors so that students can become more well-rounded and compassionate people.