A donation of $40 or more includes a subscription to the 2025-26 print issues of The Harbinger. We will mail a copy of our fall, winter, spring and graduation issues to the recipient of your choice. Your donation supports the student journalists of Algonquin Regional High School and allows our extracurricular publication to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Varying opinions on diversity in film

February 28, 2018

Like many others, I am a Star Wars fan. When I was seven years old, an at-home screening of “The Empire Strikes Back” was my introduction to mainstream cinema. Even after watching the near-abysmal second trilogy, I still remember my excitement after Disney announced a new addition to the franchise: “The Force Awakens.”

The title screen paired with the theme song prompted a sense of déjà vu, which eventually faded as a noticeable difference appeared on screen: that is, the racial diversity of characters. Though I hadn’t thought about it before, I realized that the majority of previous Star Wars actors were white. Other than playing the roles of irrelevant side characters, actors of color simply weren’t featured in past films. To say the least, I was pleasantly surprised to see two of the three main characters break that mold.

A year later, I saw it again in “Rogue One,” which featured a female lead, her male Hispanic sidekick and their multiethnic platoon of misfits.

The question had to be asked: was Star Wars trying to be progressive through its casting choices? To me, this notion seemed ridiculous – after all, they were merely hiring actors of color, not sprouting some revolutionary social movement.

Still, the push for diversity in film is nothing new. Whether it be the scathing criticism of casting Scarlett Johansson as an Asian character in “Ghost in the Shell” or the story about exposing the voices of African-American maids in “The Help,” it’s evident that Hollywood is trying to move past the “white masculine lead” trope by incorporating gender, ethnic and sexual diversity.

But the word “diversity” is so leniently employed that it seems to have become associated with broader terms like “equality” and “progress.” Realistically, I don’t think that audience members can look at “diverse” films and conclude that progress has occurred. Hollywood’s efforts of adding diversity into film are certainly a noble cause, but they don’t necessarily amount to the social progress that the industry aims to achieve.

However, senior Daphne Binto believes that diversity in film could alter the lense through which we view our world.

“There is value in [diversity in film] because what people see on screen does impact how they think and their perceptions of the world,” Binto said. “Even though film isn’t reality, it shapes how people perceive reality.”

Binto is half-Indian. She attributes cultural ignorance to naiveté in part to the portrayal of Indians on television.

“When I was in elementary school, there was me and a Chinese girl; everyone else in my school was white,” Binto said. “Kids would ask me, ‘Do you eat curry everyday for lunch?’ They asked, ‘You don’t celebrate Christmas, right? Because you must be Hindu.’ It never really bothered me too much because I assumed that they didn’t know any better. That stereotype of an Indian person was all that they saw.”

Misrepresentation or lack of representation

To make it clear, misrepresentation and lack of representation are two very different concepts. Any film depicting a generalization – dumb blonde, nerdy Asian, subservient housewife, Muslim terrorist – is a misrepresentation. For the most part, I think that the film industry has moved past that. Today, the scope of Indians in film no longer consists of only Apu from “The Simpsons”. It includes more multi-dimensional characters – Kelly Kapoor from “The Office,” Saroo from “Lion,” Cece Parekh from “New Girl,” Dev Shah from “Master of None”.

Thus, the current point of debate seems to lie in lack of representation. Of course, characters of color exist. But some often argue that there aren’t enough of them.

Senior Olivia Truong notes that although the film industry has improved itself in terms of including a broader scope of races, there is still much to be criticized about it. In particular, she believes that a role with an assigned race should be played by an actor of that same race.

“If you have Asian people play Asian characters, for example, they’ll obviously incorporate their own culture into the role and make it more authentic,” Truong said. “Film reflects the culture of our society, so if only one certain race is being reflected in film, it shows that the focus on our society is only on that race.”

Motives for diversity

A large part of the problem has to do with drawing the line between merit and incorporating diversity. If two actors, one white and one hispanic, were to audition for a role, casting directors would face a daunting question. Should they hire the white actor, who is clearly more qualified? Or do they choose the hispanic actor for the sake of avoiding backlash and giving opportunity to someone who is less privileged in the eyes of the film industry?

Truong sides with actors having more merit. This dilemma also has obvious parallels to affirmative action, a policy that some colleges use to favor students who tend to suffer from discrimination.

“I would choose the most qualified actor regardless of race,” Truong said. “The same goes for colleges – they should just pick the best applicants, race aside.”

Though the logical answer might be to hire the actor with better qualifications, the scenario is far more complex. Even if the hispanic actor were to be chosen, it would still be evident that the white actor is favored, as minority actors are generally paid much less than their white counterparts. But as long as race remains a trait that we use to judge someone’s ability and character, the problem of “merit versus minority” will continue to exist.

Now more than ever, it seems that diversity is a requisite of sorts, especially in blockbuster films that reach relatively wide audiences. But in many ways, hiring minority actors to simply “check off a box” is just as bad as avoiding diversity altogether.

“If we’re encouraging diversity for diversity’s sake, then that diversity often becomes superficial and fairly irrelevant to the actual story,” senior Alex Gowdy said.

Junior Rianna Mukherjee discussed a character named Punjab from “Annie.” It’s obvious that the filmmakers intended for Punjab to be Indian, as portrayed by his white turban and brightly colored sash. However, in the 1982 adaption, Punjab is played by Trinidadian-American actor Geoffrey Holder. This particular casting choice speaks to the idea that one minority can substitute for another and that incorporating diversity for its own sake is justified.

Relating to characters

That being said, “Annie” was released 36 years ago. With diversity being such a big deal in the film industry, many movies are critiqued based on the scope of diversity within its characters. However, diversity in this case never seems to move past physicality. Why do we feel the need to relate to movie characters based on physical appearance? Why can’t we relate to characters on the basis of intellect, personality or experience?

Gowdy argues that a character’s storyline is more important than physicality.

“What would be far more beneficial would be finding a role model in a character that is like you in more than just a superficial way: someone with the same background or family situation or childhood,” Gowdy said. “Then, I think you can relate to that character much more deeply.”

Binto believes that having a similar appearance to a character on screen may seem menial, but it actually enhances a person’s ability to subconsciously connect to that character.

“Of course you can relate to [a character’s] storyline or her development, but I think [physicality] does play a role,” Binto said. “If you look like her, you might be more apt to see those similarities.”

Additionally, the United States is a country generally known for its racially heterogeneous population. As a result, people of different ethnicities naturally tend to identify with others who resemble them. Considering that the American film industry is in the mainstream, Truong argues that it is responsible for connecting with its diverse audience.

However, Gowdy believes that relating to someone on the basis of race and appearance is quite superficial.

“I think the fact that we find it easier to relate to people of our own race is fairly trivial,” Gowdy said. “As a society, we still put an emphasis on race, both in our institutions and our public dialogue. I think that contributes to the feeling of needing to find someone of your own race to relate to, but I don’t think that’s necessary.”

Impact

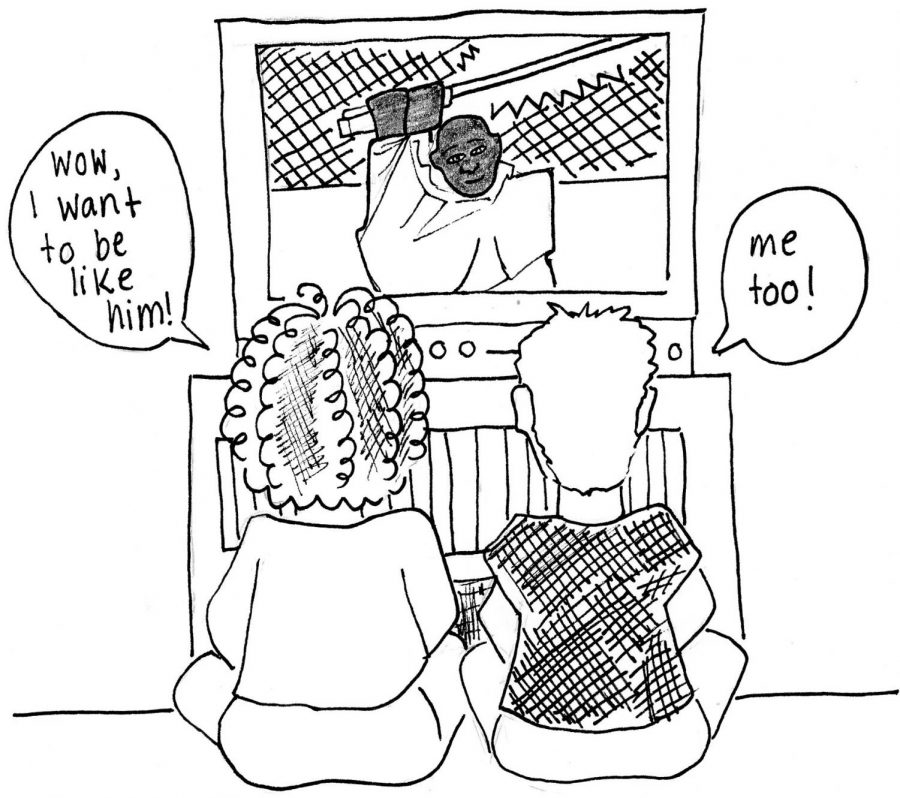

For adults, film and television serve mainly as entertainment. However, with screens being such a prevalent aspect of children’s lives, Mukherjee argues that it’s important that the entertainment industry considers its younger audiences when portraying minority characters.

“A lot of kids watch TV and that’s where they pick up on things,” Mukherjee said. “No kid is born racist; he learns to be racist.”

The debate of diversity in film has been ongoing for years, and the American film industry has made tangible strides as a result of it. But should it be something that we continuously examine in the years to come?

“I don’t think there has ever been a point at which we’ve looked at something too much,” Gowdy said. “But I think there is a danger of over-analyzing something and trying to find an issue where there isn’t one.”

On the one hand, injustice and discrimination in film has been overlooked for too long. Yet, at the same time, there comes a point when scrutinizing over issues such as this one becomes frivolous. I’m still hesitant to agree with the idea that diversity in film is actually beneficial because it should be said that film, for the most part, is woven from fiction and fantasy. All of this work to further diversity and representation in film is essentially useless if it does nothing to solve real world problems.