Leaving the past behind

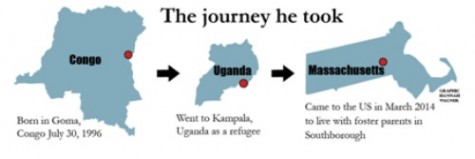

A student’s transformative journey in Congo and Uganda leads to Algonquin

Algonquin sophomore Bassam Nzovu, 18, never got the chance to bury his father. Just like every morning, on October 28, 2008, Siradji Gatanazi Nzovu went off to work at the maize flour factory he owned. But that afternoon, rebel forces rolled into Goma, a large city in eastern Congo, and changed Bassam’s life forever.

Siradji had always tried to instill strong morals into his three children. After his wife, Salam Utoni, died, he acted as a strict parent, holding Bassam and his two siblings, Ipsitam and Muntwely to tight rules. He kept a stringent 6 p.m. curfew, and punished his kids if they chose to break it. While many of Bassam’s friends walked to school, Siradji drove his son, to make sure he got there safely and on time. When Siradji wanted to watch TV, he insisted that his children keep quiet. He did not allow them to question his authority. In the eyes of Bassam, Siradji was a king.

On that day, though, Siradji would pay for his political allegiances to the Congolese government with his life. The rebels arrived at his factory and executed him, forcing Bassam, his two siblings, and their three cousins to flee Congo amidst the sound of gunshots. Bassam’s eldest cousin, [cousin], had just enough time to go to the bank to gather what he could of the family’s money before they boarded a bus bound for Uganda, leaving everything behind. Bassam does not know what exactly happened to his father, or why the rebels decided to target him and seize his home. All he knows is that his life changed forever on that fateful day.

“Suddenly you wake up in the morning and everything changes,” Bassam said, looking back. “That’s what happened that day.”

An Early Adulthood

Despite his father’s often times authoritarian rule, Bassam had a happy childhood. He attended a local Belgian-run private school, where classes were taught in French. He often crossed the nearby border into Rwanda to swim with his friends in Lake Kivu, one of the African Great Lakes. His family was well-off; they lived in a six room house with a car, an electric stove, indoor plumbing, and enough room to comfortably house the three siblings and their three cousins, with Bassam sharing a room with his younger brother, Muntwely.

“It was good, man,” Bassam said. “My father was strict, but I was happy.”

The way people think about Africa, that’s not how it is.

— Bassam Nzovu

When Bassam left Congo, he only had time to stuff some clothes into a suitcase. His cousins used the little money they had, along with aid from the United Nations, to rent a house in Kampala, the Ugandan capital. Bassam’s new house was smaller and less luxurious than the one he left in Goma. Bassam shared a room with his three male cousins and his brother, a bathroom with nine other people, and a kitchen with the rest of the housing community. In order to keep up this standard of living, though, Bassam had to work.

As a kid, Bassam could always rely on his father to supply for him, paying for his food, clothing, and other essentials. Now, though, Bassam’s cousins, all independent men in their early twenties, adopted an every-man-for-himself philosophy. Without the steady presence of his father, Bassam’s outlook on daily life changed.

“When I was in Uganda, I had to be responsible for myself,” Bassam said. “Things changed a lot. Being in a situation where you wake up in the morning, you have everything – breakfast, hot water, going to school – everything is straight. Then it changes suddenly, you’ll wake up, not even a breakfast. In Uganda, you don’t even know who to ask. My cousins, we were the same age, I couldn’t tell him I was hungry.”

Bassam got to choose between joining the workforce or going back to school, but to him, it wasn’t really a tough decision. While his cousins demanded that Bassam’s younger siblings go to school, Bassam decided, at the age of 15, to become a fulltime carwash employee.

“Going to school again was harder than getting a job,” Bassam said. “I’m not going to tell my cousin that I need a pair of shoes. It was like, ‘Now you’re a grown man, go out and get your own shoes.’ I’m not going to tell him, ‘I need some bread.’ They told me, ‘Go and get your own bread.’ I didn’t live that life before in Congo, where I used to get everything.”

As Bassam started work at the car wash, his cousins began to treat him like a fellow adult. After growing up in a strictly governed household, Bassam had his first real taste of freedom. His Muslim beliefs kept him from drinking or doing drugs, but they didn’t keep him completely out of trouble. He stayed out much later than the curfews his father had kept. Even without a license, he often drove a car. When Bassam had any encounters with police, he bribed his way out of legal trouble.

“I experienced a different lifestyle,” Bassam said. “I’m living with my cousins who were like, ‘This is wrong, this is right, but do whatever you want.’ If you choose the wrong thing, then that’s your problem. I had to be responsible for myself.”

After a few months, Bassam became tired of working at the carwash. He enrolled in English classes for six months to learn the official language of Uganda. Later, he got a job working in guest services at a bus company, helping travelers passing through Kampala with their luggage, getting travel tickets, and finding accommodations. This work experience brought him face to face with many people from Congo, reminding Bassam of his past life. Bassam’s cousins had discussed returning to Congo to try to reclaim their possessions, but nothing ever came of it.

“To go back to Congo and then go to your house and there’s someone else, and that person will tell you, “I bought this house”, and they show you every document, what would you do?” said Bassam. “We couldn’t even go back there. We lost everything.”

Exodus

Once Bassam and his cousins determined after a year in Uganda that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to return back to their life in Congo, they decided to try to immigrate to the United States as refugees. As Bassam tells it, the refugee process was difficult. First, he had to prove that his situation was dire to Ugandan immigration officials, who in turn would share it with the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and other countries accepting refugees. Then, one of these destination countries would have to admit him in another long process. Bassam estimates that, in total, the process of becoming a refugee in America took four and half years to complete.

Throughout the process, Bassam had to meet with government officials to be interviewed about his case. Bassam remembers waiting countless hours outside of government buildings, along with thousands of others seeking refugee status. Often times, he would bribe security officers outside the buildings to move up further in the line.

“The process of coming here is really hard,” Bassam said. “I don’t even know how I can explain that. Interviews every day, staying there, those offices, there are people who sleep outside waiting to meet someone to interview him. There are millions of families of refugees there. They all have the same problems, and there’s one person meeting like millions of people, so to get him to review your case, that’s a hard thing to do. You have to be sharp, and have a good case that he can read and say, ‘this guy needs help.’ And convincing him, it’s not like going there and just telling him that you’re a refugee so you need help.”

Waiting for interviews forced Bassam to miss work and a daily paycheck, making it difficult for him to attain food and other necessities.

“If we have an interview then we have to be there; we’re going to miss work and we can’t make money,” Bassam said. “If we don’t have money we’re not going to eat anything. You stay there all day, he tells you, ‘I’ll meet you tomorrow.’ Then you have to come back tomorrow. In Uganda, the way life was, you don’t work to save money. You work to save for a day. If you didn’t go to work today, you’re not going to eat tomorrow. You don’t have anything in your pocket.”

Eventually, though, Bassam’s case was accepted. He remembers his final interview, a multi-day event with the US Embassy, in which they forced him to recount his life story in detail. But at that point, he knew that his siblings and he were coming to the United States. They had been granted refugee status as foster children with Joyce and James Barton in Southborough, Massachusetts.

A New Life

Bassam always seems to have his headphones close by. Whether they’re over his ears or hanging around his neck, Bassam’s bright red Beats stand out, contrasting with the dull, dark colors of his clothes. As he steps outside into the subfreezing air, he shivers. He’s never seen snow before this year, and one can tell by the way he hunches his shoulders that the cold isn’t really for him. Nonetheless, Bassam smiles a smile that never seems to go away. He knows that he’s made it to America, and he loves his new country.

“Starting a new life, it’s not hard,” he said.

Bassam is intrigued by how many people in this country own their own cars, and about how much money everyone has. Some societal differences exist; his ESL teacher, Jennifer Cuker, remembers a time this fall when Bassam and Iptisam saw a wild turkey and they only half-jokingly remarked about catching it and cooking it for dinner. He acknowledges that there are some cultural differences between what he has experienced in the US and Africa.

Beyond that, though, a lot of things have remained constant for Bassam. The rap music he’s loved throughout his life – from Kanye West to Tupac to Biggie — has helped educate him in American slang. He watches the same TV shows, usually documentaries about history and science, and eats the same type of fast food. He remembers that when he first arrived in Southborough, his foster parents tried to teach him how to use a stove and eat with a spoon, only for Bassam to tell them that he had done both throughout his life.

“When I came here I didn’t find a big culture change,” Bassam said. “The way people think about Africa, that’s not how it is.”

Bassam has had to make some transitions. He has gone from living as an adult in Uganda to having to obey the rules of his foster parents, though he finds them much less strict than his birth father’s. A more difficult transition, though, has been the one back into a school atmosphere. He has had to start reading books and getting up early, to living the life of a teenager after living the life of a man for five years. But Bassam knows how far he has gone from running away from gunfire in Goma to sitting here in the Algonquin library. He also knows how far he has to go to create a life for himself, to recreate the sense of stability he once had in his father’s home.

“If I want a better future I have to go to school,” Bassam said. “So I tried and now I’m good with it.

Click here to read about Iptisam’s experiences in “The sibling’s perspective“

A donation of $40 or more includes a subscription to the 2023-24 print issues of The Harbinger. We will mail a copy of our fall, winter, spring and graduation issues to the recipient of your choice. Your donation supports the student journalists of Algonquin Regional High School and allows our extracurricular publication to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Dan Fishbein joined the Harbinger in 2011 as a staff writer, and became the Sports Editor later that same year. In 2012, Dan became the Harbinger's News...

Clare Strickland joined The Harbinger in early 2011 as a staff writer. She was Copy and Layout Editor for her sophomore year, Managing Editor her junior...

Natalie found a love for photography after taking a photo class her sophomore year. Since then, she has taken every possible photography class Algonquin...